The events of August 1975 that stretched on till Nov 1975 and beyond were not simply products of isolated conspiracies. They were a continuation of the historical conflicts that were at work for long, intensified in 1971 and exploded in 1975. The actors were limited in action to mostly ruling class members though the impact was universal on Bangladesh.

Apart from the cynically violent nature of the events that spanned the critical months of that year, it also showed that the ruling class was divided into factions and institutions. Some segments felt left out and applied force to step into the corridors of state power.

Such has been the analytical attitude of the 1975 events that most discussions have been about justifications and condemnations of the state power capturing whether in August or November. In both cases however, there was a continuum relating to the same institutions, whether the armed forces or the civil politicians and their inter-actions which are less touched upon.

State structure and the new paradigm

Political analysis of the events has not dealt much with the state structure as part of historical post-mortems. The discussions mostly veer towards the legitimacy of power capturing or the horrification of history itself as represented by such murders and power capturing processes, both of the killed and the killers.

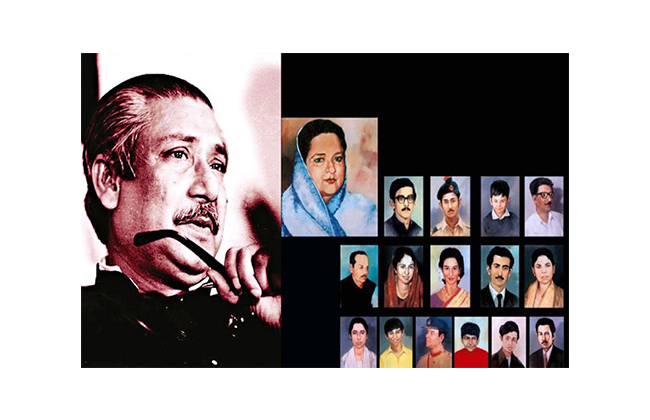

No matter what, the events of August have become a historical milestone that has defined politics in Bangladesh from then on. It has been more influential in many cases than the events of 1971. The 1975 events have become the architect and builder of the binary that dominates national political theology.

While the 1975 events were produced by various segments of the ruling class in a violent political struggle, it’s not just about politics to most. It’s germinal to a new narrative about society, history and politics and their attendant culture that has evolved into a new meta “Reality”.

The mechanics of politics, class power and ruling class dynamics that has continued to evolve over time has largely been left alone. The current political model- Us versus Them- has become a functional tool that has triumphed and is the main source of politics today.

Ruling class positioning and alliances remain much more constructive compared to the past. New formations have strengthened alliances within the ruling clusters. However, this ruling system doesn’t include ordinary people who didn’t participate in the violence of 1971. They are not part of the ruling class-then and now- but continue to uphold the ephemera of remembrances of various pasts including both 1975 and 1971 without having ruling class ambitions.

1971 -1975: The conflict phase

Many of the contributory causes of post war problems were located in the 1971 war itself including the role of the formal political and armed forces in a largely informal war caused by invasion and public resistance to it.

While people discuss physical infrastructure damage in 1971, the platform on which the state, society and its economy stood was also damaged. It was perhaps more damaged but is left out of analytical conversation.

The informal resistance that was dominant in Bangladesh from March 25 to the end April 1971 had low capacity to evolve into formal institutions of governance later after December. The result was massive societal disbalance and the rise of power groups with politics and economics intricately linked in the formal space. However, their functioning nature was informal.

The formal sector was not strengthened by the war, in fact weakened. Many people after independence thought that the 1971 war would have a socially cleansing effect on society but it didn’t. The result was the birth of the informal crony economy and political networks which dominate even now the formal institutions. And the consequent resentment of the people as well though it had low political impact.

Formal and informal: governance systems

The 1973 famine was a big reminder of how fragile the economy was or the lack of capacity to manage post war problems. Weak formal institutions couldn’t exert sufficient power on the informal players to bring down illicit economic activities. The famine was caused by several factors both national and international but the suffering of the victims was local.

The formal state forces who constituted the ruling class were in existence but political and economic power within it was not inclusively shared, some segments felt. The army was excluded from the direct ruling space and resentment grew as civilian politicians’ exerted largely monopoly control, common in a civil political state for various privileges. However, BKSAL was in some ways an attempt to resolve the problem to expand the ruling class circle of formal forces but didn’t succeed for reasons including inability to play it out over a significant period of time.

Prof. Rehman Sobhan in 2010 told the writer in an interview that the objective of Sk. Mujib in birthing BKSAL was to create a political alliance; a broad based one which would include all elements including those antagonistic to AL. He felt that it was a unification move. Alliances constitute the biggest facilitator of history is a fact but whether this model was appropriate for its time and place is not discussed.

1975- 2007: The transition phase ?

During a series of discussions on the event held on DBC TV channel in 2017,( I was present as a historian ) where both politicians and army personnel involved with the November coup participated, it seemed the interpretations of the events vary widely.

Many if not most of the discussants, many from the then army, felt that they had a duty, role and status which were higher than that of others and normal rules didn’t apply to them. They also felt left out. One ex-army officer summed up both the perspective of the military coups and the problems of institutional governance in that period. “We are not just soldiers, officers and servants of the republic. We are freedom fighters and had risked our life by fighting against the Pak army which recruited us. We took the highest risk and we can’t be treated like everyone else. “

Any discussion must take into account the fact that the subsequent army led governments were the principal governance product of August – November 1975, no matter what their motivation. It continued in one shape or other till 1990. Around this time, civilian parties who now felt excluded from the ruling space mounted a challenge and the army politicians decided against intervention as it seemed counter- productive. Ultimately this situation led to 1990’s upsurge and civilian dominated politics was restored.

Civilian politics however didn’t last beyond 2008 using their caretaker government model and the collapse saw the re-entry of the army into formal state governance. But, the situation was not feasible for this model of exclusive army- and shushil political elite rule – another variation of ruling class players and ended in 2008. A new model emerged.

2008- 2020: The alliance phase

The current model is a more functional one where the major sections of the ruling class appear to have reached an institutional understanding amongst each other regarding how the formal part of the state is to be run. In this model, the army has taken the top spot as the most established well-resourced and organized force of the ruling class but not into day to day management of the civilian aspect of the state. They are unaffected by regime change but politicians appear to be at the bottom, the one’s vulnerable to regime change. The business class is very strong and the amlas are the facilitators of state rule but increasingly play the politicians role as well. This has reduced the space for politicians triggering much internal conflict among them both internally and across the board..

This model has been shaped over time but the roots lie in both 1971 and 1975 but perhaps more in the latter. By recognizing how the present functions, one can retrieve facts about organic political governance and its realities, both positive and negative.

May every victim of August 1975 rest in peace and justice always be done.

Afsan Chowdhury is a Bangladeshi journalist, columnist and liberation war researcher. He received Bangla Academy Award in the year 2018 for his contribution to the liberation war literature.