My mindset was first awakened after reading the cover story Dr Zafarullah Chowdhury (popularly known as Zafar Bhai) and his dream hospital Gonoshastya Kendra in a defunct weekly Bichitra on 25 January 1974.

Later, on the first-page news photo in a defunct Dainik Bangla newspaper, dozens of women health workers of Gonoshastya Kendra (People’s Health Centre) from the outskirts of Dhaka, riding bicycles arrived at Central Martyrs Memorial in Dhaka to pay homage to the language martyrs on 21 February 1974.

I along with Nadira Majumder, correspondent of weekly Robbar and myself (The New Nation) regularly visited Gonoshastya Kendra in 1982 to understand Dr Zafarullah Chowdhury’s concept of his war against “drug imperialism” of the multinational companies in Bangladesh and health for all campaign.

The international drug producers were profiteering from third-world countries, like Bangladesh in over-invoicing imports of raw materials, over-pricing packaging materials and producing unnecessary medicaments.

We were doing serious research and interviews of the national committee headed by Dr Nurul Islam, Zafarullah and others when they were drafting the crucial National Drug Policy and a voluminous document reasoning for banning thousands of drugs and listing a hundred or so essential drugs which have to be produced under the generic name.

The drug policy completely knocked down the business of the multinational companies in Bangladesh. The drug policy for the first time was pinned on the world map for a pro-people initiative.

Despite the drug policy being severely criticised by drug producers and hundreds of doctors, the military dictator General HM Ershad went ahead with full steam to implement the policy.

Several ambassadors spoke to the government to delay the implementation, citing unemployment of hundreds and thousands of employees and the shortage of drugs in the market which will jeopardise the healthcare system in the country.

Zafarullah was confident and so was the Health Ministry admitting that there will be a shortage of drugs in the market and could be replenished from the competitive world market.

Gonoshastya Kendra believed in alternative healthcare which needs to reach the rural areas, where people cannot afford it and most importantly where rural people have never seen a doctor in their life.

The centre produced thousands of barefoot doctors mostly women, recruited from rural areas. They went to remote inaccessible regions to provide healthcare to pregnant women, children and treatment of elderly people.

The concept of barefoot healthcare medics encouraged the government to launch a nationwide primary healthcare programme. The best example is the nationwide child immunisation drive by the government by trained paramedics. Child immunisation was much higher than the World Health Organisation (WHO) target of 75% and Bangladesh attained between 93% and 98% every year since 2005.

Well, fearing the doctors and physicians will be posted in rural areas, away from the luxuries of city hospitals, the Bangladesh Medical Association vehemently opposed the national primary healthcare programme.

The medical doctors’ apex body criticising the programme said it takes several years to train a doctor and a couple of years for nurses (including internship), therefore the mobilisation of medics will be a major challenge.

Zafarullah scoffed at their criticism and said it is possible to train barefoot medics within six months, who can perform delivery of infants including obstructive births.

The world’s largest NGO, BRAC partnered with Gonoshastya Kendra to train thousands of medics to cover millions of the population in villages.

The drug policy buoyed the massive growth of home-grown medicament entrepreneurs who are presently producing drugs in Bangladesh and exporting to more than 150 countries worth US$163.83 million (2021-22).

No other medical colleges or para-medic training institutions in Bangladesh have compulsory field (rural) training experience, except for those under Gonoshastya Trust.

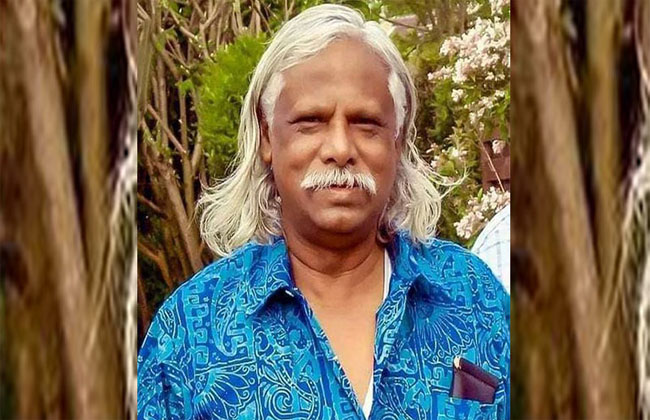

The 82-year-old doctor of the poor had the vision to reach the rural poor to ensure that the global ‘Health For All’ campaign was meaningful.

When the health message of smoking-related diseases was not known to many, his institution was a pioneer to announce job opportunities and even for students in medical college and para-medics, with a strict note in red letters that only non-smokers should apply.

The patient’s suffering, agony and pain caused by smoking-related disease is widespread. The government’s ban on smoking in public has not been able to deter people from smoking, ignoring the harms of nicotine and second-hand smoke.

Well, besides a series of successes, he has had a few failures in his life. He attempted to bring about a change in politicking and government, which he miserably failed. In 1981, he wanted to form a coalition of the left-leaning, muktijuddhas (liberation war veterans) and mainstream Awami League to support his candidate, a liberation war hero General MAG Osmany for the president.

The plan was scuttled and a major setback in the presidential campaign when Awami League nominated constitutional author Dr Kamal Hossain as their candidate for the election against Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) candidate Justice Abdus Sattar who obviously won with a wide margin.

Zafarullah did not have any properties or business in his or his family’s name anywhere. All the institutions and establishments are under Gonoshastya Trust. He left behind the entire country to mourn his death but left behind his legacy of pro-people healthcare institutions.

Saleem Samad is an award-winning independent journalist, media rights defender, recipient of Ashoka Fellowship and Hellman-Hammett Award. He could be reached at <saleemsamad@hotmail.com>; Twitter @saleemsamad