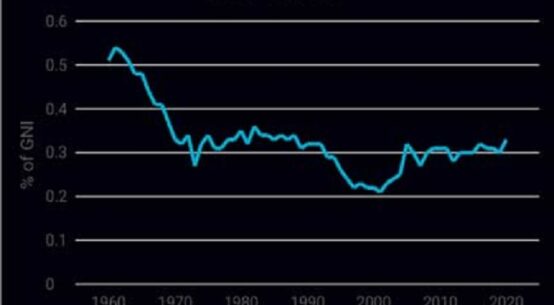

Bangladesh has become increasingly indebted since 2009. The country’s external debt stock increased from US$23.3 billion in 2008 to US$100.6 billion in December 2023 (see figure below). Thanks to the country’s mega-projects led so-called development with borrowed money under the now deposed authoritarian regime of Sheikh Hasina.

The new government should urgently put a moratorium on debt re-payments using UN Security Council resolution 1483 that granted a debt-shield to prevent creditors from suing the government of Iraq to collect sovereign debt. The new government then initiate an independent review of all debt contracts under the autocratic regime to determine beneficial uses of incurred debts. The review should declare the proportion that was wasted through corruptions or used for financing repressions of the regimes as “odious”.

Odious debt is a concept in international law that refers to debt “incurred by rulers who borrowed without the people’s consent and used the funds either to repress the people or for personal gain”. There are moral, economic and legal arguments for not re-paying the odious portion of debts.

Autocrat’s debt bonanza

Bangladesh’s average external debt stock jumped from US$10.7 billion over more than 3 decades (1972-2008) to US$52.6 billion during 2009-2023 when Hasina’s autocratic regime consolidated power by unprecedented machinating three consecutive elections, making State institutions partisan and unleashing brutal repressions.

Corruptions, money laundering, and poor project management as well as selections meant that the revenue flows or returns from these mega-projects are far less than what is required for servicing the debt. Gross external debt-GDP ratio increased from around 28% in 2016 to around 37% in 2023. Likewise, external debt-export earnings ratio increased from 56.3% in 2016 to 116.6% in 2023. These key indicators indicate that Bangladesh is heading for a corruption induced debt crisis, temporarily given respite by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The IMF’s loan will have to be repaid with interests; paying debts by borrowing; or using one line of credit to pay for another line of credit cannot be sustained for long. There are better ways to deal with unstainable debts, especially when the indebtedness is due to creditors’ continued lending despite well documented evidence that the borrowed money is misused and siphoned off the country.

Irresponsible lending is odious

Lenders should be held responsible for irresponsible lending knowing the extent of corruption, misuse and repression in the country, and that the borrowed money was providing a life-line to a highly corrupt and repressive regime. The debt-funded mega projects were used by the regime to legitimize its misrule and suppression of people’s democratic rights. Such debts are odious.

Such debts are odious, and violet the “Principles on Promoting Responsible Sovereign Lending and Borrowing”, developed by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). These Principles demand that lenders refuse to lend to the regime, thus preventing wasteful or harmful spending. These Principles not only make a repressive regime less likely to survive, but also ensure debt sustainability.

Core international legal norms and principles, such as Good Faith, Transparency, Impartiality, Legitimacy and Sustainability are applied in the UNCTAD Roadmap and Guide to Sovereign Debt Workout Mechanisms and in the UN General Assembly resolution A/RES/69/319 on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes, adopted in September 2015.

Moral, economic and legal arguments for repudiating odious debts

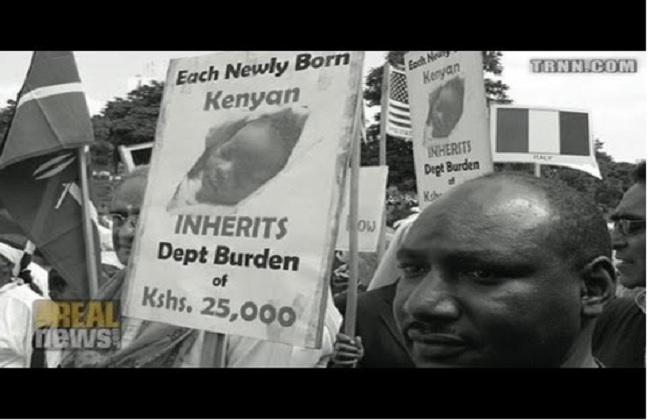

The prospect of yoking innocent generations of citizens to the repayment of a corrupt and repressive regime’s profligate debt is simply distasteful; morally repugnant; economically untenable, and legally indefensible.

The moral case for repudiating odious debts arises from the premise that some regimes are so repugnant that they should be actively condemned by the international community. The world should not stand by silently as a regime murders its own people or loots the country’s wealth while ordinary citizens starve.

The economic justification for repudiating odious debts rests on the prospect of increasing the welfare of the country in at least three ways: (1) there will be a lower debt burden to service; (2) odious regimes, which reduce welfare, are less likely to emerge; and (3) should they emerge, they are less likely to survive for a long time.

The legal argument for repudiating odious debts is consistent with the accepted view that equity constitutes part of the content of “the general principles of law of civilized nations”, one of the fundamental sources of international law stipulated in the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Thus, the international law obligation to repay debt can never be absolute, and has been frequently limited or qualified by a range of equitable considerations, some of which may be regrouped under the concept of “odiousness.”

In many countries legally individuals do not have to repay if others fraudulently borrow in their name, and corporations are not liable for contracts that their chief executive officers or other agents agree to without any authority.

An analogous legal argument is: sovereign debt incurred without people’s consent and not benefiting the people should not be transferable to a successor government, especially if creditors are aware of these facts in advance.

Historical precedence

The doctrine of odious debt originated in 1898 after the Spanish-American War. The United States argued during peace negotiations that neither it nor Cuba should be held responsible for debt the colonial rulers had incurred without the consent of the Cuban people and not used for their benefit.

Other historical cases of repudiating odious debts include: Soviet repudiation of Tsarist debts; Treaty of Versailles (1919) and Polish debts; Tinoco arbitration (1923) – (Great Britain vs Costa Rica); German repudiation of Austrian debts (1938); Treaty of Peace with Italy (1947).

In recent decades, major shareholders forced the IMF to cut all lending to the former President of Croatia, Franjo Tudjman, in 1997, after he was accused of resorting to political violence and appropriating public funds.

The Khulumani Support Group, representing 32,000 individuals who were “victims of state-sanctioned torture, murder, rape, arbitrary detention and inhumane treatment” filed a law suit in 2002 in the New York Eastern District Court against 8 banks and 12 transnational companies demanding apartheid reparations.

In 2003, the concept of odious debts was used by the US to argue for cancelling Iraq’s debts of over US$125 billion incurred by Saddam Hussain after his overthrow. It was argued that such debt not only impeded a successful rebuilding of post-authoritarian States, but that the debts were never legitimate inheritances of the new government.

Treasury Secretary John Snow held “the people of Iraq should not be saddled with those debts incurred through the regime of a dictator who has now gone.” Undersecretary of Defence Paul Wolfowitz emphasised that much of the money borrowed by the Iraqi regime had been used “to buy weapons and to build palaces and to build instruments of oppression.”

After an evaluation, the Government of Norway in 2006 determined that obligations arising out of lending to certain developing countries as part of the Ship Export Campaign of 1976–1980, and guaranteed through the Norwegian Institute for Export Credits, should be cancelled on grounds that Norway ought to share responsibility with debtor countries for the programme’s failure.

The Norwegian case is not an example of “odious debt”, but is due to the notion of co-responsibility and reflect the idea that repayment may be subject to broader considerations of the equities of the debtor–creditor relationship.

What needs to be done

The Interim Government of Bangladesh should immediately put a stop to external debt servicing and request the UN Secretary-General to set up an UN-led independent commission to review all debts incurred by the repressive autocratic regime that it replaced. The UN-led review commission must not include lenders – multilateral and bilateral – due to likely conflict of interest, especially when they irresponsibly continued to lend to the regime, knowing its corruptions and usurpation of democracy.

This requires political will as powerful countries and international financial institutions may be offended.

The people have expressed their strong will to build a new country based on the principles of accountability, fairness, equity, inclusiveness and justice.

The burden of odious debts of the repressive regime and irresponsible lendings must not weigh on rebuilding of a new Bangladesh.

Anis Chowdhury, Emeritus Professor, Western Sydney University (Australia) & former Director of UN-ESCAP’s Macroeconomic Policy & Development Division.

Khalilur Rahman, former Secretary of the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Technology Bank for LDCs; former head of UNCTAD’s Trade Analysis Branch and its New York Office.

Ziauddin Hyder, Adjunct Professor, University of the Philippines at Los Banos and former Senior Health Specialist, World Bank