Sheikh Sirajul Islam, a smallholder farmer in Bangladesh’s southwestern Satkhira district, sowed the wet-season aman rice in his four acres of land this August. He is hopeful for a good yield, he says.

Sirajul, from Satkhira’s Shyamnagar upazila, resumed rice cultivation two years ago, after having stopped it for two decades. During these two decades, he commercially farmed shrimp in a marine water enclosure — locally called gher — which initially seemed profitable. However, after gradually facing a loss from aquaculture, the 53-year-old, whose family have been rice farmers professionally for generations, switched back to agriculture.

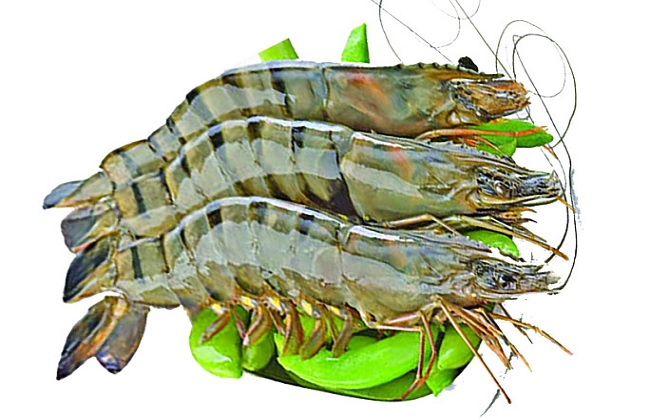

He tells Mongabay that the shrimp production dwindled due to viral outbreaks, while excessive soil salinity barred him from cultivating other crops around the shrimp enclosure.

Like Sirajul, many smallholder farmers in Bangladesh’s coastal districts, especially in the southwest, like Satkhira, Khulna and Bagerhat, are turning back to agriculture as an adaptation strategy to combat climate change impacts due to rising sea-level and temperatures.

Instead of a monoculture of shrimp, they now cultivate aman rice during the peak monsoon season, and different fruits like watermelon, oil seeds like sunflower and mustard, maize, various vegetables, boro rice, and other crops during the dry season, optimizing the alluvial lands around the year. “Now, I cultivate rice during the monsoon season and vegetables or fruits in the dry season on the same land that was exposed to high salinity earlier,” Sirajul says.

A few years ago, Abdullah Harun Chowdhury, an environmental science faculty member at Khulna University, supervised a study on the transition from shrimp to rice farming in coastal Bangladesh.

Harun observed that smallholder farmers, re-engaged in agriculture, are no longer allowing saline water from intertidal rivers which they previously did to fill their ghers. “By preventing salinity intrusion, they are producing food for family members. They are also restoring greenery to their near-deserted environment,” Harun says.

Crop diversification is the key

In coastal Bangladesh, livelihoods based on shrimp, fish and rice cultivation face growing risks from climate change-induced sea level rise, extreme flooding, cyclones, erosion and salinization.

In such conditions, crop diversification is considered an adaptation strategy for smallholder farmers to reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience. Although crop diversification in Bangladesh remains low in the other parts of the country, it is on the rise in coastal areas, according to a recent study.

Following interviews with farmers from a few selected localities across the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta in Bangladesh, researchers have traced the prevalence of intensified crop diversification in the shrimp cultivation zones.

Government data on agricultural output also matches the study findings.

In five years since the 2018-19 fiscal year, Khulna, Bagerhat and Satkhira districts recorded an 11-14% increase in aman rice production.

During this period, farmers in three districts amplified the production of vegetables by around 50%. Compared to the yield in 2018-19, the production of sunflower seeds, mustard and maize increased in 2022-23 in the three districts, with Khulna ranking the highest.

During the five years, Khulna and Satkhira recorded 197% and 114% increase in fruit production, respectively, while watermelon production grew by 6-10 times in the three districts, as the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) data shows. Besides, watermelon, mango, coconut, guava and banana are also considered cash crops in the region.

Recently, some researchers have noticed a growing trend of profitable intercropping of vegetables and rice in the region.

Among the vegetables were radish, eggplant, tomato, beans, green peas, kohlrabi, drumstick, cauliflower, cabbage, plantain, carrot, okra, potato, taro, leafy greens and various cucurbits, including bottle gourd, pointed gourd, spiny gourd, bitter gourd, pumpkin and cucumber.

DAE’s Khulna divisional chief Bivas Chandra Saha observes that smallholder farmers consider cropland as their only means of livelihood, while many of them no longer want saltwater intrusion to disrupt agriculture for the entire year.

“Crop diversification and increased production are the reflections of their will,” Bivas tells Mongabay.

Where salinity determines livelihoods

For years, salinity has been the common enemy of agriculture in southwest Bangladesh. The Dutch-style polders or dykes, built in the 1960s to protect farmland from saline intrusion, were initially effective.

The Farakka Barrage in West Bengal, India, on the Ganga River close to Bangladesh’s border started worsening the salinity problems by reducing water flow, especially during the dry season, in the major distributaries including the Gorai, Kobadak, Pasur and Shibsa — the lifelines of the country’s southwest region’s agriculture.

In the 1980s, commercial shrimp cultivation took off in this region, forcing rice farmers to switch to shrimp farming, as the increasing salinity made year-round rice cultivation difficult.

Following the trend, smallholder farmer Nirmal Gayen, based in Dakop, Khulna, had no option but to switch to shrimp aquaculture, as he failed to protect his land from saltwater intrusion.

However, in the last couple of years, shrimp farming has been impacted by frequent flooding during cyclones and viral outbreaks exacerbated by the varying temperatures, among other manifestations of climate change.

“The last time I cultured shrimps, I could only recover half of the $705 (60,000 taka) I had invested. I incurred losses because viral diseases frequently attacked my shrimp farm,” recollects Nirmal, who switched to profitable rice-watermelon farming a few years ago.

A study at Dakop estimates that the gross benefit and net income are higher in rice-watermelon agriculture than in shrimp farming alone.

Statistics on shrimp culture reveal that five major watermelon-producing districts, Khulna, Patuakhali, Bhola, Barguna and Noakhali, produced approximately 30,000 tons of shrimp in the 2018-19 fiscal year.

However, by 2022–23, shrimp production had declined by over 7%, with shrimp farming coverage shrinking by nearly 5%. Khulna alone recorded an 8% decrease in shrimp production.

Water scarcity challenges crop diversification

People in coastal Bangladesh, particularly the southwestern region, mostly avail freshwater from during the monsoon.

Studies reveal that surface water salinity remains high in these regions, and peaks from February to April, coinciding with the farming of summer-time crops.

During the post-monsoon season, farmers break the canals’ connectivity to intertidal rivers with temporary embankments, restricting saline water intrusion into the crop fields. The reserved water is later used for irrigation in the dry season.

However, Sirajul expresses his concerns, “An acute water shortage persists here during summer. Whatever little water remains available in the rain-fed ponds and canals, we use it for watering the growing crops. But sometimes, even that becomes unmanageable.”

Mohammad Shamsudduha, a professor in the department of risk and disaster reduction in University College London, says that salinity continues to threaten the soil and water in Bangladesh’s coastal regions.

Reserved during the monsoon, the water is later used for irrigation in the dry season.

Reserved during the monsoon, the water is later used for irrigation in the dry season. Image by Noor A. Alam.

To ensure sustainable water management and agricultural productivity, he recommends that existing small rivers and canals be rejuvenated or newly excavated to capture rainwater during the monsoon season. Moreover, he believes that adaptation strategies should address seasonal variations in soil and river water salinity, as well as the seasonal impacts of tropical cyclones, to enhance climate resilience.

“Continuous monitoring and regular assessment and adjustments to these strategies are essential in mitigating the long-term effects of sea level rise and saltwater intrusion,” Shamsudduha says.

(This article was republished from The Mongabay under Creative Commons License)

Sadiqur Rahman is a Bangladesh-based journalist. His 12-plus-year career in journalism includes wide reporting wide reporting on climate change, biodiversity conservation and livelihood-related issues.