Pakistan’s economy is in deep crisis and things are deteriorating fast. Many problems have domestic causes, but these are being compounded by global trends.

As any non-resident Pakistani can tell you, calls for cash or in-kind donations for struggling families have been circling and increasing online for several months. Masses of people are obviously in desperate need – and that includes people who believed they had achieved long-term middle-class status.

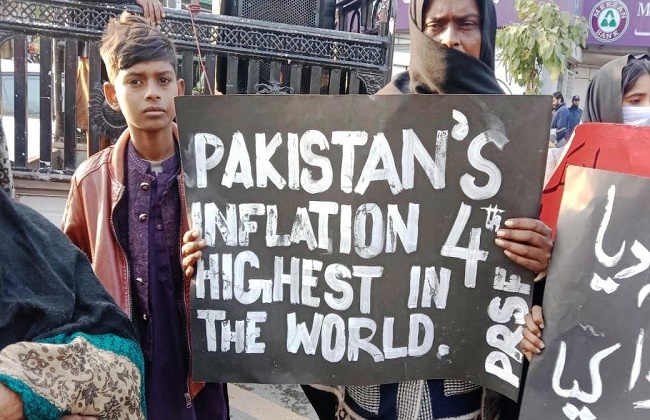

On 1 April 2023, a Reuters headline read: “Pakistan records highest-ever annual inflation; stampedes for food kill 16”. Indeed, millions of Pakistanis are struggling to put food on their tables. Emergency centres for food distribution are seeing strong demand, with people occasionally being crushed to death in the crowds. More generally, buying fruit is now considered a luxury, even in the holy month of Ramadan, when most Pakistani families fast in the daytime, but normally enjoy special treats after dusk. Women and girls in particular are suffering, as typically happens in crisis settings.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the annual food-price inflation rate was at about 50 % in March, above consumer price inflation at 35 %. The growth outlook is bleak. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects a mere 0.5 % for this financial year. The World Bank forecasts 0.4 % and the Asian Development Bank 0.6 %. Only a few months ago, the prognosis was more optimistic. In October, the IMF still reckoned GDP would expand by 3.5 % (after six percent in the previous financial year).

The country must also cope with an energy crisis. Even nationwide power outages now feel common. Pakistan’s economy depends on imported fuel, including for the generation of electric power. The dwindling of foreign-exchange reserves is therefore alarming. The current $4 billion will suffice for at most one month of imports. The government was forced to stop non-essential imports in the winter, which further slowed down industrial activity, as some inputs and components are no longer available.

Moreover, the country is being weighed down by its huge foreign debt. Debt Justice, a campaign group, reckons that debt servicing will cost the government 47 % of its revenues this year. The government owes foreign institutions about $ 100 billion. Roughly one-third of the total consists of loans from China, including state-owned commercial banks.

In view of the urgent problems, Pakistan’s only recourse is IMF funding and further loans from “friendly countries”. But relations with the IMF are difficult. New money from China or the Gulf States, however, would only provide short-term relief at the cost of compounding long-term problems.

Tense relations with the IMF

The IMF is not happy with how Pakistan’s economy has been mismanaged and the state of macroeconomic fundamentals. IMF officers, of course, are aware of a long history of bailouts that did not lead to sustainable results.

Pakistan is currently supported by an IMF Extended Fund Facility (EEF). Of $6.5 billion, $3.9 billion have been disbursed. The IMF concluded this EEF agreement with the government of former prime minister Imran Khan. The rules state that Pakistan’s policymakers must achieve pre-defined targets of macroeconomic stability, with indicators set for things like fiscal discipline and debt sustainability. These rules required the government to cut spending, which would have meant hardship – especially as a quarter of Pakistan’s people lived below the poverty line even before the current crisis struck. But things have not gone according to plan. Pakistan missed several of the macroeconomic targets last year.

To some extent, the reason was global events, which the government could not control. The climate crisis mattered very much. The country first suffered a terrible heatwave and then unprecedented flooding in 2022. There was widespread damage to lives, livelihoods and infrastructure. Among other things, the cotton crop suffered – and that exacerbated the balance of payment crisis. Textile exports are an important source of revenue. The government was forced to use public funds to provide relief. International institutions are aware of this fact and donors have pledged relief money. It is also undisputed that the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent spike in oil and food prices have exerted additional pressure on Pakistan.

Domestic policy failure

However, macroeconomic targets were also missed for domestic political reasons. Prime Minister Khan and his party, the PTI (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf), fell out of favour with the country’s defence establishment. In a desperate attempt to remain in power, Khan rolled out fuel subsidies and tax amnesties. These schemes strained both the national budget and the forex reserves, but they did not help Khan to stay in office.

The parliament ousted Khan in a vote of no confidence and a new government came to power in April 2022. It is based on a complicated multi-party coalition. However, under Shehbaz Sharif, the new prime minister, the fuel subsidy was not rolled back. The new government actually worsened a difficult situation by pegging the Pakistani rupee to the dollar. The official exchange rate remains artificially high and the black market is thriving. People are increasingly opting for informal financial services, weakening the formal financial system.

Observers, including those at international finance institutions, generally accept that Pakistan has become overwhelmed by events beyond its control. Nonetheless, IMF officers are aware of recurring policy failures and have reason to wonder whether any Pakistani government will ever live up to its promises.

The full truth is that Pakistan’s military is over-developed, but its tax system is under-developed. State institutions do not enjoy much popular trust. It does not help that the governing coalition looks weak. It may well lose the general election that must be held later this year. How the polls will play out, is difficult to predict. In turbulent times, anything can happen.

Chinese loans amount to about $30 billion

Pakistan’s largest bilateral creditor by far is China. The bilateral debt amounts to about $30 billion and is linked to infrastructure projects. The “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” is part of Beijing’s international Belt and Road Initiative. Some of the projects are of military relevance, though most obviously serve developmental needs. China has started to provide balance-of-payment loans. However, the public is not fully informed of the details. Loans come with comparatively high-interest rates.

Pakistan needs all the support it can get. It would help if the IMF and China acted in a coordinated manner. So far, they are not. Some Pakistanis hope that the country’s geographic location, size and nuclear arms will always lead to strategic advantages. Neither China nor the USA wants to lose influence after all. The current situation, however, is untenable.

Decades of inept governance, political instability and geopolitical manoeuvring have contributed to the current situation, which is being exacerbated by climate change and inflation. Global trends and home-grown problems have added up to create a perfect storm.

Sundus Saleemi is a senior researcher at Bonn University’s Centre for Development Research (ZEF)