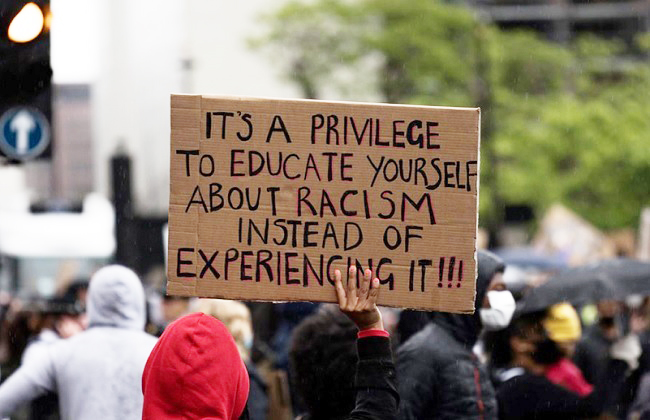

As we commemorate the 103rd anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre this month, organizations and communities should focus on white privilege as it is a critical but often overlooked component of effective racial justice change processes. White privilege, rooted in European-led colonization, provides unearned advantages to white individuals, often unnoticed due to their perception as universal experiences.

In 1988, American scholar and activist Peggy McIntosh famously defined white privilege as: “The unquestioned and unearned set of advantages, entitlements, benefits and choices bestowed upon people solely because they are white. Generally, white people who experience such privilege do so without being conscious of it.”

Operating within institutions, policies, and societal norms, white privilege perpetuates racial disparities on interpersonal and systemic levels. These structures, ingrained in globalization, sustain racist mindsets, enabling economic, political, and cultural hierarchies that benefit white communities. Dismantling such systemic privilege is complex as it is deeply embedded in modern societal structures.

White privilege is a concept that extends beyond the borders of the United States and Europe. Recognizing how white privilege operates worldwide is essential for meaningful change within organizations, social structures and communities. Discussions of global governance often omit race.

However, it is imprudent to ignore how racist views influence major decisions, including acts of aggression against perceived inferiors and vulnerable communities. Having white privilege and recognizing it is not racist as white privilege exists because of historic, enduring racism and biases.

During the General Assembly’s observance of the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination on 21 March 2024 United Nations (UN) Secretary-General António Guterres emphasized that, “Racism is an evil infecting countries and societies around the world – a deeply entrenched legacy of colonialism and enslavement. The results are devastating: opportunities stolen; dignity denied; rights violated; lives taken and lives destroyed. Racism is rife, but it impacts communities differently.” He highlighted the persistence of racism globally, stemming from centuries of colonialism, enslavement, and discriminatory practices.

The establishment of the UN in 1945 occurred during a time when much of the world was under European colonial rule, leading to a dominant influence of colonial and former enslaving powers in its creation. This is reflected in the composition of the UN Security Council (UNSC) that plays a central role in maintaining global peace and security.

Particularly, the five permanent members, known as the P5, are the victors of World War II: the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China. Among them, three are Western nations, and four are majority-White countries, while China is the only non-Western, non-majority-White member.

The P5 holds veto power, enabling it to block any significant resolution, regardless of widespread support from other member states. This privileged status originates from the post-World War II era, positioning the P5 members as the primary decision-makers in global security matters.

While the UN, as an international organization, employs a diverse workforce from various countries and backgrounds, white privilege still manifests within the UN system. The composition of staffing within the organizations of the UN system mirrors a pattern as in the UNSC.

Among the professional staff in UN organizations, there is a visible disproportionate parity between the West and the rest of the world. Out of five regional groups of the UN member states — Western European and Other States, African States, Asia-Pacific States, Eastern European States, Latin American and Caribbean States — staff from Western European and Other States (including the United States of America and Canda) constitute more than half of the population of professional staff in the UN system. This disparity, directly and indirectly, contributes to the current organizational culture that enables racism and racial discrimination within the UN.

The JIU review on racism and racial discrimination found that staff from predominantly non-white countries in the global South tend to occupy lower-paid positions and wield less decision-making authority compared to their counterparts from predominantly white countries. Personnel identifying as Black/African descent, South Asian, or Middle Eastern/North African face prolonged career advancement timelines, contrasting with quicker progress for those identifying as white.

This racial discrimination in seniority and authority has emerged as a macro-structural issue to be addressed. The survey conducted by the UN Asia Network for Diversity and Inclusion (UN-ANDI) on racism and racial discrimination highlighted that discrimination, both subtle and overt, further divides staff from developed and developing nations within the UN, perpetuating notions of superiority and privilege. These dynamics, rooted in historical legacies of slavery and colonialism, impact recruitment, promotion, performance evaluation, and workload distribution within the organization.

Acknowledging white privilege is a crucial step toward addressing racism within the UN. It involves recognizing the inherent advantages that white individuals have due to the color of their skin and understanding that white privilege exists within the UN organizations.

This can be achieved by staff those identifying as white through learning, self-reflection, listening to marginalized voices, promoting empathy, challenging the status quo, collaborating with diverse groups, becoming an ally, and advocating for organizational change. While discussions around white privilege may be uncomfortable, the focus should be on implementing structural changes within the organization.

In the collective endeavor to eradicate racism within the UN, acknowledging white privilege stands as a fundamental component of the solution. The UN organizations must develop strategies to utilize white privilege to promote equality and dismantle systemic racism and biases within their institutions. Leveraging white privilege can be a powerful tool in creating a fairer and more just environment within the UN.

Shihana Mohamed, a Sri Lankan