Created in 2016, the Mexican Caribbean Biosphere Reserve (MCBR) hosts 1900 species of animals and plants and contains half of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the second largest in the world after Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

This ecosystem is under pressure from the construction of two of the seven routes of the Maya Train (TM), the Mexican government’s flagship megaproject, whose construction, which began in 2020, alters the environment of the Maya Forest, the largest tropical rainforest in Latin America after the Amazon.

This is recognized in two technical reports obtained in Mexico by IPS through public information requests, which state that, although the project is outside the marine area itself, it is located within its zone of influence.

Regarding the 257-km section 4, a document from October 2021 acknowledges the impact on two high priority hydrological regions.

And with respect to the impact on the 110-km section 5, another document dated from May 2022 states that “there is no previous study or information on the monitoring and sampling sites. The presence and state of the fauna that inhabit the trees are unknown.”

The MCBR administration recognizes impacts on two priority marine regions and on the coastline of the southeastern state of Quintana Roo, which is protected by the reserve.

For this reason, the MCBR refused to issue a technical opinion on section 5 due to lack of “sufficient information and elements” and, for T4, issued an opinion that demanded the presentation of additional data and prevention, management, and oversight measures.

Despite the impact that the railroad will have in the region, the government’s National Fund for Tourism Development (Fonatur) did not request reports from at least four other nature reserves.

Fonatur will be in charge of the TM, which will run for some 1,500 kilometers, with 21 stations and 14 stops, through five states in southern and southeastern Mexico.

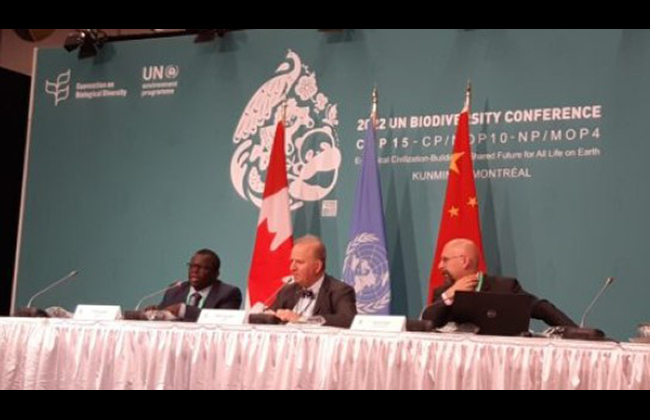

The case of the railway exemplifies the contradictions between the attempt to protect nature and the development of infrastructure that sabotages that aim, a theme present at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which began on Dec. 7 in the Canadian city of Montreal and is due to end on Dec. 19.

Moreover, the railway’s cost of some 15 billion dollars is classified as forming part of the harmful subsidies to biodiversity, which total 542 billion dollars a year globally. The investment needed for the conservation and sustainable use of nature is estimated at 967 billion dollars a year.

In the post-2020 global biodiversity framework, which is due to be adopted at the summit, one of the main 21 measures being negotiated is called in UN jargon 30×30: the protection of 30 percent of the planet’s marine and terrestrial areas through conservation measures by 2030, in an attempt to halt the loss of biodiversity on the planet.

The plan has attracted support from more than 100 countries but has awakened distrust among indigenous peoples, who have suffered from the imposition of natural protected areas without due information and consultation.

The summit, which has brought together some 15,000 people representing governments, non-governmental organizations, academia, international organizations and companies, will also discuss the post-2020 global framework, financing for conservation and guidelines on digital sequencing of genetic material, degraded ecosystems, protected areas, endangered species, the role of corporations and gender equality.

The 196 States Parties to the CBD, in force since 1993 and whose slogan at this year’s COP is “Ecological civilization. Building a shared future for all life on earth”, have not yet agreed in Montreal on the percentage of the oceans that should be protected and whether it should include waters under international jurisdiction.

The global framework is to succeed the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, adopted in 2010 in that Japanese city during the CBD COP10 and due to be met by 2020, which have failed. Target 11 stipulated the protection of 17 percent of terrestrial areas and inland waters and 10 percent of marine and coastal areas.

Insufficient rules

Manuel Pulgar Vidal of Peru, WWF global leader of Climate and Energy, who is attending COP15, said the problem lies in the regulation of protected areas.

“Nations such as Colombia, Ecuador and Chile have strengthened the system of natural areas. But in general the systems are weak and need to be reinforced, and money, staff and regulations are needed,” he told IPS.

Mexico has 185 protected areas, covering almost 91 million hectares -19 percent of the national territory-, six of which are marine areas, encompassing 69 million hectares. Despite their importance, the Mexican government dedicated less than one dollar per hectare to their protection in 2022.

In addition, management plans have not been updated to cover works such as the Maya Train.

Colombia, meanwhile, protects 15 percent of its territory in 1,483 protected areas covering 35.5 million hectares, including 12 million hectares in marine areas.

Chile, for its part, has 106 protected areas covering 15 million hectares of land – 20 percent of the total surface area – and 105 million hectares in the sea, in 22 of the conservation areas.

Among the 49 governments that make up the High Ambition Coalition (HAC) for Nature and People, aimed at promoting 30×30, are 10 Latin American countries: Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and Peru.

Of the 586 commitments that organizations, companies and individuals have already made voluntarily at COP15, held at the Palais des Congrès in Montreal, only 93 deal with marine, coastal and freshwater ecosystems, while 294 address terrestrial ecosystem conservation and restoration; 185 involve alliances and partnerships; and climate change adaptation and emission reductions are the focus of 155.

Aleksandar Rankovic of the international NGO Avaaz said the key challenge goes beyond a specific protection figure.

“The hows are not in the debate. It’s up to each country how it will implement it. It’s left to each country to decide what’s appropriate. There is little openness on how to achieve the goals,” the activist from the U.S.-based organization dedicated to citizen activism on issues of global interest, such as biodiversity, told IPS.

Only eight percent of the world’s oceans are protected and only seven percent are protected from fishing activities. Avaaz calls for the care of 50 percent of marine and terrestrial areas, with the direct participation of indigenous peoples.

The protection of marine areas is tied to other international instruments, such as the Global Ocean Treaty, which nations have been negotiating since 2018 within the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and which aims to protect 30 percent of these ecosystems by 2030.

Pulgar Vidal, for his part, called for the approval of the 30×30 scheme. “Implementing these initiatives takes time. And you need an international financing mechanism,” he stressed.

In Rankovic’s view, a strong global framework is needed. “The issue is broader, because fisheries are not well regulated. Without this, marine areas will be part of a weak program,” he warned.

COP15 has also coincided with the 10th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety and the 4th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization, both components of the CBD and part of its architecture for preserving biodiversity.

Emilio Godoy has been a journalist since 1996. He studied literature at Del Valle University of Guatemala and a master’s degree in communication and development at City University in London.