When a Chinese rocket malfunctioned shortly after launch in April 2020, destroying Indonesia’s $220 million Nusantara-2 satellite, it was a blow to the archipelago’s efforts to strengthen its communication networks. But it presented an opportunity for one man.

Elon Musk – the owner of SpaceX, the world’s most successful rocket launcher – seized on the failure to prevail over state-owned China Great Wall Industry Corp (CGWIC) as Jakarta’s company of choice for putting satellites into space.

The Chinese contractor had courted Indonesia – Southeast Asia’s largest economy and a key space growth market – with cheap financing, promises of broad support for its space ambitions and the geopolitical heft of Beijing.

A senior government official and two industry officials in Jakarta familiar with the matter told Reuters the malfunction marked a turning point for Indonesia to move away from Chinese space contractors in favour of companies owned by Musk.

Nusantara-2 was the second satellite launch awarded by Indonesia to CGWIC, matching the two carried out by SpaceX at that time. Since its failure, SpaceX has launched two Indonesian satellites, with a third set for Tuesday; China has handled none.

SpaceX edged out Beijing through a combination of launch reliability, cheaper reusable rockets, and the personal relationship Musk nurtured with Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Reuters found. Following a meeting between the two men in Texas in 2022, SpaceX also won regulatory approval for its Starlink satellite internet service.

The SpaceX deals mark a rare instance of a Western company making inroads in Indonesia, whose telecommunications sector is dominated by Chinese companies that offer low costs and easy financing. The successes came after Indonesia resisted U.S. pressure to abandon its deals with Chinese tech giant Huawei, citing its dependence on Beijing’s technology.

Details of this shift, which were described to Reuters by a dozen people, including Indonesian and U.S. officials, industry players and analysts, have not previously been reported. Some of them spoke on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorised to talk to media.

“SpaceX has never failed in launching our satellites,” said Sri Sanggrama Aradea, head of the satellite infrastructure division at BAKTI, an Indonesian communications ministry agency.

The April 2020 incident makes it “hard” for Jakarta to turn to CGWIC again, he added.

SpaceX, CGWIC and Pasifik Satelit Nusantara – a key shareholder in the Nusantara-2 project – did not respond to questions for this story.

China’s Foreign Ministry said in response to Reuters questions that “Chinese aerospace enterprises are continuing their space cooperation with Indonesia in various forms.” It did not elaborate.

Presidential office spokesperson Ari Dwipayana said the government prioritises efficient and capable technology that meets the need of Indonesians when awarding contracts.

The tussle between SpaceX and China offers a window into a much larger battle to dominate a rapidly expanding space industry.

The global satellite market – including manufacturing, services and launches – was worth $281 billion in 2022, or 73% of all space business, according to U.S. consultancy BryceTech.

China launched a record 67 rockets last year, out of 223 globally, according to a report by Harvard professor and orbital tracker Jonathan McDowell. The vast majority were launched by CGWIC.

That put China only behind the United States, which had 109 launches, 90% of which were done by SpaceX, the report found.

Washington and Beijing are also competing over satellite-based communications networks.

SpaceX’s Starlink, which owns around 60% of the roughly 7,500 satellites orbiting earth, is dominant in the satellite internet sphere. But, last year, China began launching satellites for its rival Guowang broadband mega-constellation.

U.S. military officials have said China wants to use satellites and space technology to spy on rivals and increase military capabilities.

China’s Foreign Ministry said in a statement to Reuters the U.S. allegations were a smear and that Washington was using the concerns as a pretext to expand its influence in space.

Unlike its Chinese counterpart, NASA relies primarily on privately owned rockets from firms such as SpaceX, which has billions of dollars in U.S. government contracts.

But the U.S. government and military are concerned about their reliance on SpaceX, especially given Musk’s muscular business style, according to one current and one former U.S. official working on space policy.

While legacy U.S. defence contractors like Boeing (BA.N), opens new tab and Lockheed Martin (LMT.N), opens new tab typically consult the State Department before making foreign deals, Musk and SpaceX dealt directly with Jakarta, the two officials said.

In response to Reuters’ questions, a Lockheed Martin spokesperson said the company “works closely with the U.S. Government, our allied nations and international customers”. Boeing declined to comment and the State Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Pentagon spokesperson Jeff Jurgensen declined to answer specific questions about SpaceX, but said the Department of Defense’s “many space industry partnerships have a proven track record of success”.

Nicholas Eftimiades, a former U.S. intelligence officer and expert on Chinese espionage operations at the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank, said SpaceX’s CEO had ruffled some feathers in the U.S. capital: “Elon Musk does things his way and some officials don’t like that”.

Nonetheless, Musk’s deals bucked a long-running trend of Western firms losing out to Chinese businesses in Indonesia, a sprawling archipelago of over 17,000 islands that is home to more than 270 million people.

Widodo said in October that Beijing is set to become the largest foreign direct investor in Indonesia within two years, surpassing Singapore.

Chinese companies dominate the internet and 5G market, so Beijing was the obvious partner for satellite launches until the 2020 incident, said Andry Satrio Nugroho, an economist at the Jakarta-based Institute for Development of Economics and Finance think-tank.

“Indonesia has a close relationship with China across many sectors. It’s difficult to break China’s dominance.”

In May 2022, Jokowi, as the powerful Indonesian president is popularly known, visited a SpaceX facility in Boca Chica, Texas.

“Welcome to Starbase,” Musk said, smiling and shaking hands with the president, who was seeking Tesla investment in Indonesia’s nickel sector.

Widodo’s two-hour visit included 30 minutes of talks with Musk at an office packed with miniature rockets and then a tour of the production area, according to an Indonesian official with direct knowledge.

The president has long sought to build an EV industry in Indonesia, which has the world’s biggest reserves of nickel, a key element in electric batteries. The term-limited leader leaves office in October, but experts say Widodo will remain a major power broker after the candidate he tacitly supported to be his successor claimed victory in the Feb. 14 presidential election.

Widodo told Reuters last year that to woo Musk, he has also offered tax breaks, a concession to mine nickel and a subsidy scheme on EV purchases. But a Tesla EV or battery factory in Indonesia, which Widodo has publicly asked for, have not materialised.

Instead, days after the trip, according to a source with direct knowledge, Indonesian officials began discussing another of Musk’s businesses: Starlink.

During the Texas meeting, Musk asked Widodo to let Starlink into Indonesia, the source said.

Telkomsat, a subsidiary of state-owned telecoms firm Telkom, was supportive, its former chief executive Endi Fitri Herlianto told Reuters.

For months, the telco had sought regulatory approval so that Telkomsat could use Starlink services for cellular backhaul, or connecting mobile base stations to its network, Herlianto said.

Officials were concerned about the potential impact on domestic telcos if a permit was granted. The plan made no headway – until the Boca Chica visit.

Less than a month after the Texas meeting, Telkom announced its subsidiary had received Starlink landing rights.

Indonesia’s communication ministry told Reuters that Starlink is only permitted to operate a backhaul service with Telkomsat and that it does not have the right to retail consumer internet services.

Musk “put that ask on the table then and there, so things started,” said the source with knowledge of Indonesian discussions, referring to the May meeting.

Widodo’s spokesperson, Dwipayana, confirmed that Musk and the president discussed opportunities in Indonesia, adding that officials are still in communication with the billionaire about future investments by his businesses, including Tesla.

Telkom did not respond to requests for comment.

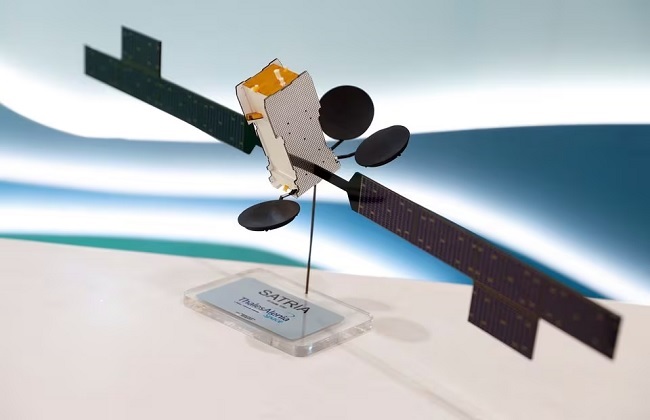

Last June, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket pushed into orbit the 4.5-tonne Satellite of the Republic of Indonesia (SATRIA-1) – Southeast Asia’s largest satellite.

Nia Satwika, a SATRIA-1 project manager, said SpaceX offered lower costs and had higher availability of launch slots when compared with other operators.

“They are a game changer,” she said, referring to SpaceX’s ability to reuse parts of its rockets – a crucial cost advantage over rivals.